This week I’m working on the structural design of three different concrete foundations for three pre-engineered metal buildings (PEMB) in the state of Texas. All three soils reports indicated that expansive soils were going to be a factor in the foundation design and all three reports gave recommendations for both Drilled Pier foundations and Shallow Slab on Grade foundations with imported fill material. This is a situation we often face across the Front Range here in Colorado as well. In my career, about half of the contractors I have worked with believe that it is more cost effective to build a Drilled Pier foundation than to a Shallow Slab on Grade Foundation with Imported Soils and the other half believe the opposite.

For those unfamiliar, there are some soils that will actually increase or decrease in volume when there is a change in the soils moisture content. These volume changes can cause a building’s foundation to move, resulting in repair or stabilization costs to the owner. There are several ways for a structural designer to avoid this. The two we will be discussing are described below:

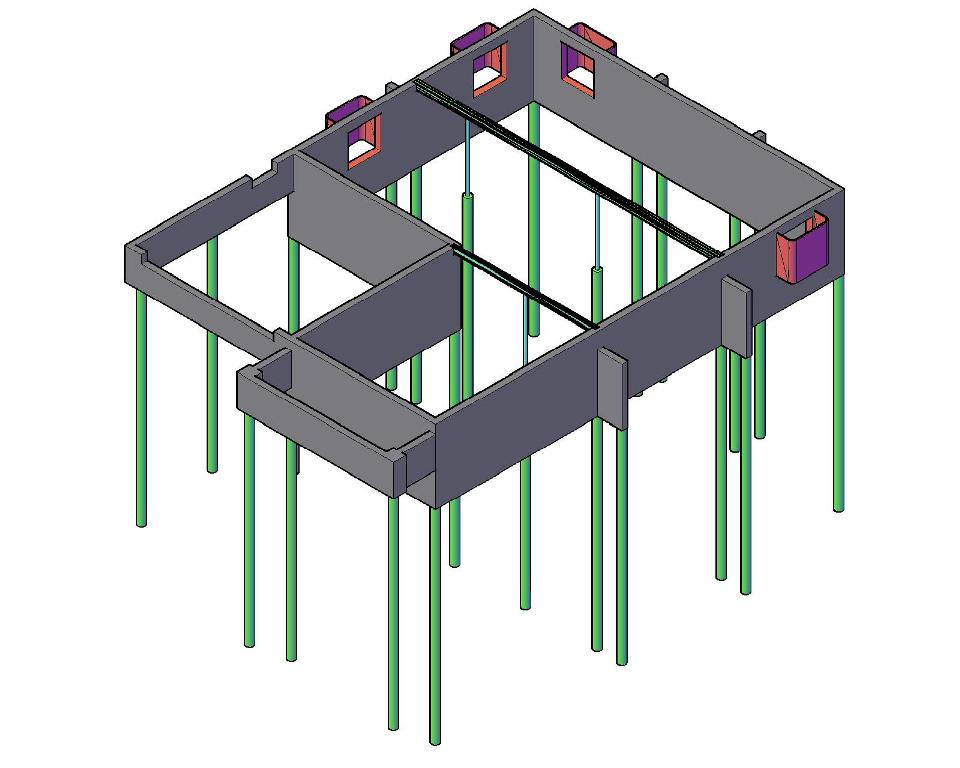

Drilled Pier Foundation: Deep piers are drilled into the ground through the layer of expansive soil into the “better” soils below. These piers are filled with concrete and will support a “grade beam”, which is essentially the foundation wall. The benefits of this design are that the final product has an extremely low risk of foundation movement and the foundation walls may be constructed narrower because they do not have continuous bearing. The disadvantage of this design is that a suspended “structural” floor (that will not bear on the expansive soils) must be constructed.

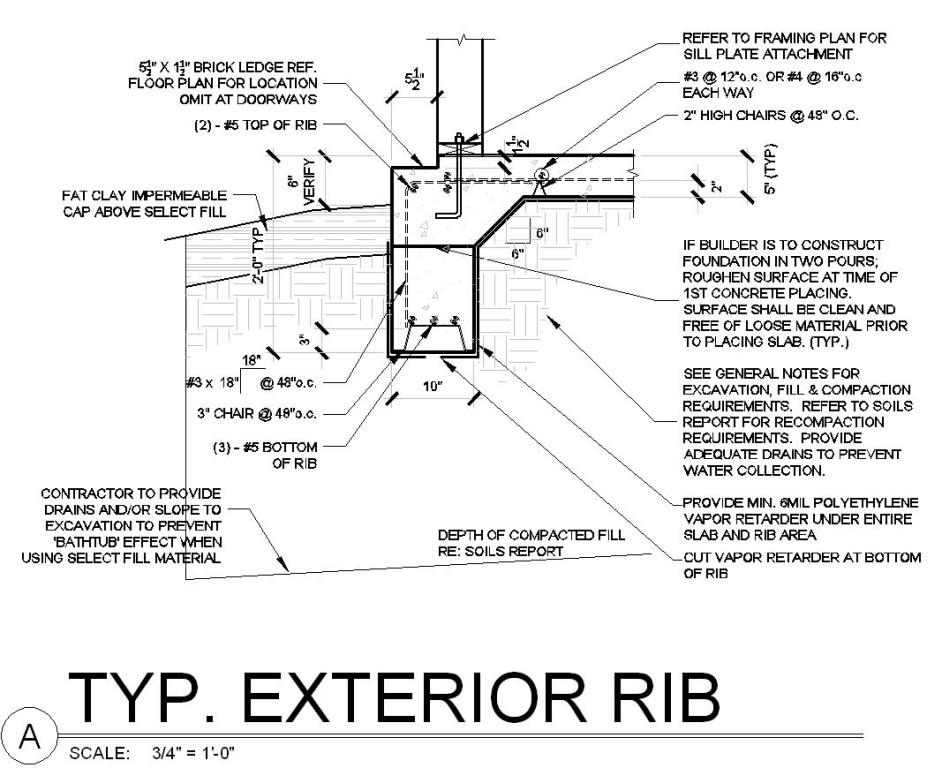

Slab On Grade Foundation with Imported Fill: One way to avoid the negative effects of expansive soils is to just get rid of them! This design requires the builder to remove the top three to six feet of the undesirable soil and replace it with imported soil that is non-expansive. The benefit of this design is that allows for a shallow foundation with mild reinforcement requirements because the load is transmitted directly to the soils. Additionally, the floor can be a concrete slab bearing directly on ground. The disadvantages of this design are there will still be some risk of foundation movement, added costs of importing new soil, placement and compaction of the imported soil, and testing to ensure proper compaction. The foundation walls themselves may also need to be constructed wider to ensure adequate bearing pressures. (A load spread out over a wider base exerts less pressure than the same load concentrated through a narrow base. You can test this at home by resting the weight of your hand on a bowl of Jello brand gelatin desert. I like to use the cherry flavor in my structural experiments. Try it once resting the full weight of your hand with once with your palm stretched out flat and once balancing the weight of you hand on your index finger.)

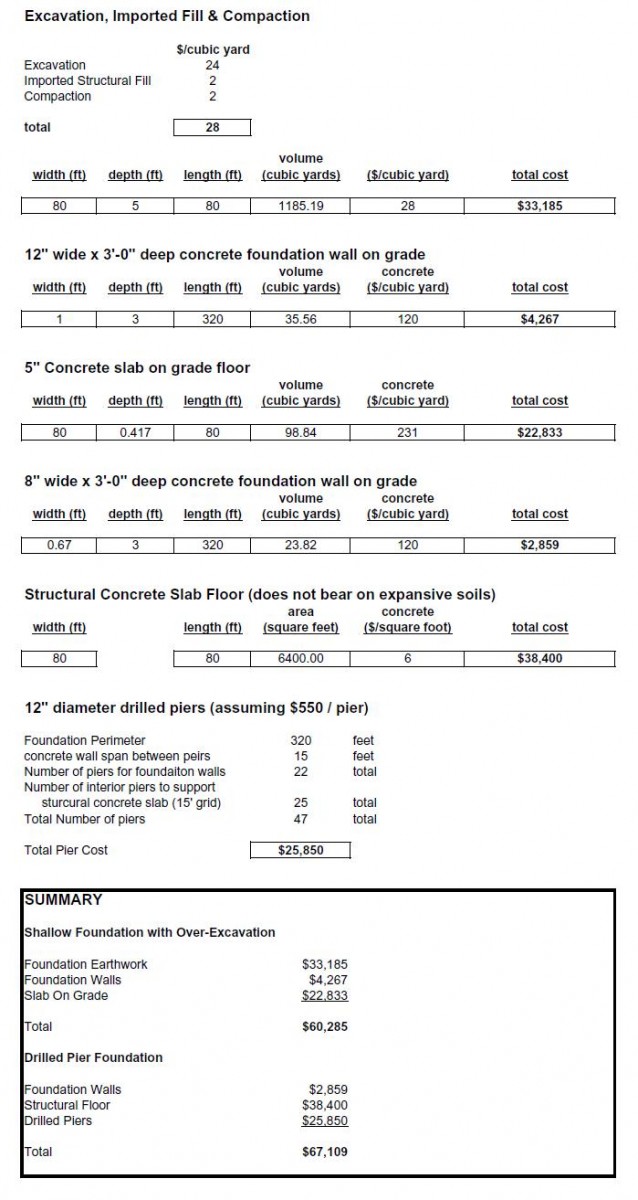

Using cost information gathered from RSMeans, I came up with simplified (read: VERY simplified) spreadsheet below. The Slab on Grade appears to be the more cost effective solution, but only by a margin of approximately 10%. I admit there many, many more factors to consider than I present in this article. Factors such as the depth of expansive soils, the magnitude soil’s expansiveness and the local costs of importing suitable fill material could easily shift our results one way or the other. My hope is to spark a debate among our readers to help focus our design considerations so that we might be able to present a more definitive answer in the future.

Assumptions:

- Single story commercial building, 80’ x 80’ square.

- Excessive floor movement cannot be tolerated due to the building’s intended use.

- Existing soils exhibit a potential foundation movement of 3 ½”; over excavation and replacement of soils to a depth of 5’ will reduce potential movement to an acceptable 1” to 1 ½” movement.