Out for a summer bike ride with my son one day, we found ourselves at the top of a winding downhill path through a park lined by green grass being gently misted by the park’s sprinkler system. As we started down the hill, memories of running through the sprinklers at the park across the street from my childhood home came to mind. But like so many other childhood rites-of-passage, our sprinklered oasis involved a modern facet. There was a sign posted to advise that water used in the park was non-potable. So much for a refreshing douse of natural cooling.

A growing population, greenhouse gases, global warming – all familiar monikers seemingly indicative of a dubious future for our children’s children. And water, perhaps our most precious resource, has been subject to increasing demand for decades. The use of non-potable water is a responsible decision, but what does it mean?

Most people are familiar with potable water, or “drinking water” – it’s the water that comes out of your sink faucet, and typically provided by a municipality. But how is that different from non-potable water? It’s a matter of treatment level. While water filtration and distribution systems have been under development for centuries, large scale sand, and more modernly chemical, UV and reverse osmosis filtration, have set the standard for water that can be consumed with minimal risk of illness. Non-potable water, on the other hand, is an encompassing term that includes everything not for drinking, with varied levels of treatment.

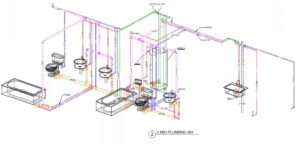

Some municipalities distribute non-potable water separately from potable water to be used specifically for toilet flushing and irrigation. This type of system is sometimes called recycled water and is often a part of a municipality’s storm system. Typically, it’s moderately treated to eliminate airborne contaminants, and is not up to the standards of drinking water.

Rainwater collected and reused used for irrigation on-site is usually called rainwater reuse, or harvested rainwater, and falls into the category of on-site non-potable water. Treatment is minimal to non-existent, so long as storage is adequately confined.

Somewhat confusingly, grey water is also considered on-site non-potable water, but there’s an important distinction: grey water is generally that which comes from a shower or bathroom sink drain, and is then collected and used to flush toilets or, with some chemical or separation treatment, to water a lawn.

Yet another type of non-potable water is reclaimed water, or black water. These terms refer to former sewage that is treated and used for irrigation and other non-drinking water purposes. As there is a higher level of treatment required, these systems are not common on a small scale. However, they are gaining traction in drier climates and will likely be an important part of efficient building design in the future.

This brings us back to potable water. When reclaimed water is reintroduced to the environment (referred to as an environmental buffer in water treatment terms), and then recollected and treated for drinking, it is called de facto reuse water. Most potable water in the U.S. falls into this category.

Since the amount of water recovered is inversely proportional to the level of treatment and resources required for such treatment, the use of non-potable water is one of many important tools in energy conservation. As evidence of the growing popularity of such systems, Chapter 13 of the 2012 International Plumbing Code (IPC) was added to begin to define these systems and provide guidelines to protect public health. Changes to the 2015 IPC include further definition and more specific requirements. This trend will continue as non-potable water plays an increasingly important role in our use of building systems in the future.