We are working on a LEED Platinum housing project and have been doing a tremendous amount of research on both SIP and ICF construction. For the uninitiated, SIP construction (Structural Insulated Panels) is a construction method where rigid insulation is sandwiched between sheets of OSB sheathing, creating a thermally broken solid wall form. ICF construction (Insulated Concrete Form) is a method where rigid insulation makes up the permanent forms for a poured concrete wall. Both systems are extremely airtight and both are systems that provide thermal breaks in the walls. Very important things for a highly sustainable design.

Our findings so far:

In order to get the full points for LEED credit, we need to either have a mass wall (ICF) with an actual (not performance) R-value of at least R-14. This is easily done with just about any thickness of ICF wall because the foam insulation is where the value is really calculated. You get actual R-17 to R-22 depending on the ICF block – “equivalent” r-values are touted in the 40’s and 50’s, but that includes the thermal mass equivalency and is really an apples-to-bananas comparison anyway, so don’t believe everything you hear.

For SIPs, we wouldn’t consider that a mass wall, so the actual R-value needs to be a minimum of R-21. Again, easy to do in a 6-1/2” SIP panel (which would be R-42 – way over everything else by comparison). If we have poured concrete floors inside the building, then we have plenty of thermal mass inside the home (where we really want it), and not separated by a layer of insulation (which is one of the complaints with ICF).

Both systems are thermally broken systems as far as LEED is concerned. Both systems will be very high performance for airtightness (and will require an HRV). It appears that only SIPs will allow us additional LEED points for pre-built panel assemblies since ICFs are site-built assemblies that are then poured on site. We’re still researching that with LEED though, so I will validate that and amend this post when we have more data on that.

Space is also a fairly large consideration as well. LEED calculates the area from the outside face of the rough assembly, so the additional thickness required by ICFs will add approximately 120-150 sq.ft. of wall thickness for a 2,000 sq.ft. footprint. I know that sounds crazy, but there is quite a bit of square footage tied up in our exterior walls that isn’t useable, and the thicker the walls, the more that hurts our ability to keep the space functional and stay within the LEED guidelines that won’t require us to add additional points to our requirements total. So, to maximize LEED points, it’s not enough for a wall to perform thermally, it also needs to do it with minimum wall thickness – now we really are talking the 21st century modern home here!

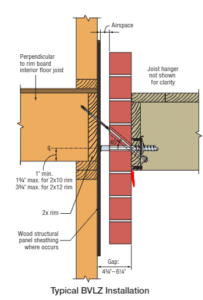

Chances are, any sustainably built low-rise Type V building project will have both ICF and SIP components, it really is a question of “how much ICF and how much SIP”. Right now, unless there is some major economic advantage in the initial cost for using ICFs, the information I have is telling me to build the foundation with ICF and use ICF for walkout basement conditions if site topography warrants it. Then run the SIPs from the main level floor up.

This will also allow you to handle common details more easily. For example, you can set the foundation wall to the inside face of the sip so that it can act as a ledge for stone or brick veneer while preserving the thermal break. It’s also worth noting that angles other than 90 degrees at the building corners are easily done with SIPs and won’t pose any problems with designs that are customized. In fact, just about any shape is possible with SIPs – even curved forms. You can do those angles with ICF as well, but it isn’t a lot of fun, so you want to minimize those kinds of design features wherever possible.

It’s also worth noting that there are a lot of good reasons to plan for SIP walls running through the building, separating key areas as they provide great thermal separation and sound attenuation in the same space as a conventional stud wall.

We actually started this project thinking that we would need to go to ICFs in order to maximize our LEED point potential, however, it turns out that SIPs actually have a slight advantage when it comes to LEED because of their reduced thickness. For all intents and purposes, they will perform equally in a LEED thermal analysis though, so unless you can build an ICF wall for less than a SIP wall, the SIP wall would be the best choice.

If you are looking to have a highly sustainable building designed, this information is only one very small part of the comprehensive analysis for the great number and variety of design decisions, and all of these choices must be tailored to your specific situation, location, and site adaptation. With that said, we strongly urge you to engage the services of a design professional that has the knowledge and experience so that the financial investment in your building is validated and actually performs. In fact, in order to get LEED certification, you are required to assemble a design team that has those qualifications. Contact EVstudio if you have any questions or need to discuss your next sustainable project.

For more SIP info read my post Top 10 Important Things to Know About SIPs

11 thoughts on “ICF vs. SIP…The Debate Continues”

Thanks Frank for your comment, the original post is for general ICF and SIP systems. I did not analyze any specific products for ICF or SIP in this discussion, but you raise some interesting points. There are indeed some proprietary ICF and SIP products out there that address some of the known issues, and at the end of the day, the cost/value trade offs available to specific systems available to a particular market should be studied. Thus, the debate continues…

I have also been researching the subject as a custom home builder. Dean has evaluated both products and came up with flaws on each that I believe have been nullified by an ICF that he may have not included.

The Apex Block product stand alone is r-52 rated and I am told will get an actual R-35 after concrete is poured. This product is thermally broken and for Leed points they claim up to 22. The block is 10″ thick taking up wall space and may effect LEED points but as a bonus at least in Tx. the state comptroller will not allow the counties to count the extra 6″ in the square footage calculations for size of home in valuations.

The other ICF’s that are sandwich built seem much more difficult to put together than the Apex “lego” style contruction. Looks like they would also take more steel, more labor and 3 times more concrete. I’ve seen burn test at 3 hours on their website and a C-4 blast test, so I think there is no structural flaws there either.

I think it would be overall easier with SIP’s but with wood vs bugs, renting a crane and difficult mechanical installation the Apex looks real easy! I guess my question to Dean is whether this type ICF is considered in your results as explained. Frank

Hi Ethan,

The ICF foundation wall will be providing insulation between the heated space of the home and whatever is on the other side. In the Winter months, if the constant temperature of the earth in your climate is higher than the ambient air temperature above ground, then a bermed home will help lower winter heating costs. Similarly, if the earth temp is lower than ambient in Summer months, then cooling costs will be lower. The fact that the wall itself is insulated simply means that the transfer of heat through the wall to the earth is controlled (which is what you want). You wouldn’t want an uninsulated wall in an earth-bermed structure as 55 degrees (avg earth temp in the Colorado climate) is generally uncomfortable for habitation. Hope that helps!

I was hoping somebody could give me some advice and perhaps a quick explanation:

If I plan on building a bermed house to take advantage of the constant temperature of the ground, would using ICFs beat the purpose? The house willl be built in Seattle, WA.

Thanks for cluing me in!

-Ethan

“Dean,

I read with interest your Oct 31, 2008 post of a Platinum LEED construction (https://evstudio.com/2008/10/31/icf-vs-sipthe-debate-continues/) and I am wondering what you finally decided with respect to LEED points in the SIPs versus ICF comparison.

My wife and I are hoping to build a superinsulated home and try for Gold LEED. We’ve priced out both ICF and SIPs and, of course, SIPs are much more affordable.

I think our architect and our final builder (bids due in soon) would like to know how your superinsulation format worked with LEED.

Thanks,

Duke”

Hi Duke,

Thank you for your interest in the article. Our experience with both SIPs AND ICFs is that they both will result in a very tight thermal envelope, and that is where the LEED points will come in. As far as that is concerned, I would consider them as equals when it comes to the thermal envelope. The energy model that your engineer will need to do in order to get submit for the LEED certification may show the ICFs to perform a bit better overall, mainly because of the thermal mass they bring to the equation. However, because that thermal mass is insulated from the interior space by the interior side of the form, it is far less effective than if it were in the conditioned space. So, again, the SIPs turn out to be a better value for the money, and every bit as tight and superinsulated as the ICF system.

On a related note, be sure to include an HRV (heat recovery ventilation system) in the home when using either SIPs or ICFs as the superinsulated envelope will not “breathe”, and therefore will require mechanical ventilation.

Good luck with your project and feel free to contact us or have your contractor or architect call or e-mail if you or they have any other questions. Thanks!!

-Dean

Pingback: Different Structural Foundation Types | EVstudio Architecture, Engineering & Planning | Blog | Denver & Evergreen | Colorado & Texas Architect

HomeWrights has been a part of 14 ICF Home Projects and 4 projects where SIP panels were used. While we are impressed with the performance of both products, there’s one thing we tell our clients who are considering these materials for residential construction. Be prepared for sticker shock! These methods are MORE expensive than conventional construction. Superior to be sure, at least from an energy standpoint, but more expensive by anywhere from 10 to 30%.

ICF homes we’ve done have the feel of a fortress – a very energy efficient fortress. There is absolutely no sound transfer from the outside. You can immediately sense that you’re in a more substantial home. And the energy performance that our clients have noticed has been phenomenal. One client who built a 5200 square foot ranch home in Berthoud using ICF is bragging about utility monthly energy costs in the $20’s and $30’s, not the several hundred dollars you’d spend to heat or cool a conventional home. By the way, his garage is also ICF construction, and its got a heated floor. SIP panels likewise provide some pretty amazing energy performance. And they do go up quick.

Again, the only negative I can say about either product is the cost. The additional cost is not really related to the product itself – but to the trades that have to adjust their thinking when working on a concrete structure, or on a panel built structure. Framers, electricians, plumbers, heating contractors, roofing contractors, truss manufacturers, etc, all have to re-think their approach, their tooling, and the fasteners they use. That adjustment on their part drives up cost.

My perspective for clients is this: If this is a legacy home – one that you intend to occupy for a decade or more – its worth the extra dollars – or alternatively, its worth it to sacrifice square footage for a superior product. Of course, we should all be thinking more long term these days, so that point of view has to be considered as well .

One last thought. Mary and I built our home of 2 by 6’s, and we insulated with Icynene expanding foam in the walls. Our exterior walls are R-28, and the effective R value is higher because there are no air leaks, especially at the vulnerable points, like rim joist, or truss to wall connections. Granted, there’s more thermal bridging, but our house is amazingly energy efficient, and very, very, very quiet. My point is this, the stepping stone between conventional construction with fiberglass insulation and ICF or SIP construction is a conventionally framed house with spray in foam. I’m confident that this approach would withstand a very detailed scrutiny comparing cost to build, cost to maintain, and cost to heat / cool, and it would prove to be the most sensible approach for the “typical American family” that occupies a home for 7 years.

Some great information on both the SIPs and ICF. I have built with both and both are an excellent choice for energy effecient structures and noise reduction. They are both priced about the same in my area of AZ. So what makes the choice clear?

A concrete wall will still be standing in 500 years, unharmed by termites or anything else. I have seen the testing on wall systems using the tornadoe test (firing a 2×6 at 120 MPH from a canon) and only the ICF wall passed the test with undisputed results.

SIPs still remain “glued together” with what? Probably a little harmful to health issues. I would rather build with SIPS than conventional framing, don’t get me wrong.

As far as assembled on site? Blocks like Build Block are shipped assembled, so stack them and away you go. Check it out on http://www.buildblock.com you’ll be impressed with the added features.

Either way, good luck!

By the way, there is a great guest article on Jetson Green about how affordable prefab doesn’t really exist – however, he makes an argument for “hybrid pre-fab”. SIP’s fit into this category.

http://www.jetsongreen.com/2008/09/prefab-is-not-t.html

Interesting and informative-especially how these wall systems pertain to LEED. We just completed our first house with SIPs and came away with the following:

-Not many “flat-lander” builders know how to build with them, so any efficiencies will be not be reflected in their framing numbers (SIPs appear to be used more in the mountains)

-It’s very nice to be able to fully review shop drawings and correct mistakes BEFORE the house is framed. With standard stick-built projects, there is usually no way to review compliance with your drawings until it’s been built (and in some cases it’s too late)

-Electrical in exterior walls – our panels had standard races, but it was still a major pain for the electrician to pull wires, so we paid a premium

-Some jurisdictions may require a structural calculations book submitted as part of the document set

Overall, I think we will use the panels again. The extremely tight construction combined with nearly perfectly plumb walls results IMHO a vastly superior exterior envelope system for your home.

Nice discussion of SIP benefits. I designed and built a SIP in 2003. I like it very much. Unfortunately so do various creatures. Carpenter ants find it excellent, before I could get the siding up Flickers (woodpeckers) found that sips are much like a dead tree. Hard on the outside and soft on the inside. So I would just suggest that you seal everything very well and keep a eye out for intrusion.

Otherwise the energy benefits are great. I am also in the thinking stages of my next project and am thinking about using SIP for the floor and ceiling wiht Straw bales for walls, but not structural. I would use some type of post for structure.

The greatest benefit of SIP over ICF is how quick you are working inside. My two story SIP took 1.5 days to put up. After that rain or heat was not much of a issue. Also my huge number of windows and doors took less than a day to set as everything “just fit”. I had the window/door manufacturer talk directly with the SIP manufacturer for opening sizes.

Another benefit of SIPs is the rigidity of the material. I put some tile down without backer board to see how it held up. Four years later it is still working well. Also I find that I have had no nail popping on the siding since the walls do not seem to move at all, even in the strongest wind.

Comments are closed.